Heads

The head of a case or cartridge is the lower part of the cartridge case that holds the primer and seats against the bolt face. It’s where the head stamps – maker’s marks – are found. It is not a bullet, ever. Bullets are exactly that: bullets. Anyone that calls a bullet a head is, at best, ill-informed but more usually plain deluded and stupid to keep on doing so after learning otherwise. Heads and headspacing are critically important and should never be confused.

Headspace

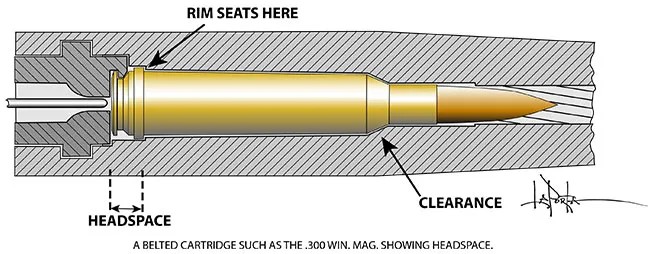

Headspace is defined as the distance between the face of the bolt and a point in the chamber that prevents further forward movement of a cartridge. In effect, it is a measure of the amount of free space or slack present in the chamber that allows for cases of very slightly different size, for example from different manufacturers running at different ends of the tolerance band, still to chamber. In military rifles, headspace may be a little larger than in civilian sporting or target rifles to allow for chamber wear or dirty ammunition.

Note that headspace refers to the free space availed for seating the cartridge , and so is yet another reason why one should not refer to bullets as ‘heads’

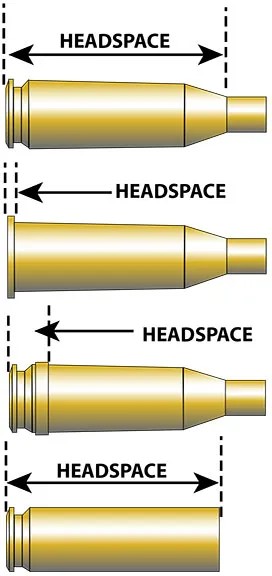

Note also that different types of cartridge headspace against different parts of the case. A rimmed case spaces on the rim, most pistol cased space against the neck, belted magnums seat on their belt and so forth. These options are shown on the diagram below.

Headspace can be checked with “Go” and “No-go” gauges. These are precision machined gauges that replicate the specified minimum and maxim sizes of a cartridge. The bolt on a firearm must be able to close with no resistance when a Go gauge is inserted into the chamber. This signifies that the firearm is able to meet the minimum length specification for that particular cartridge. If the bolt does not close with the Go gauge inserted, the firearm has insufficient headspace. Another possible cause could be a dirty chamber or bolt face. The accumulated dirt may be thick enough to prevent the bolt from closing on the gauge.

However, if the firearm is clean and the bolt still does not close on the Go gauge, it must be taken to a competent gunsmith for adjustments.

If a firearm successfully closes on the Go gauge, at a minimum, the firearm has sufficient headspace. However, it may still have excessive headspace. That can be determined with No-go gauge. A new (or overhauled) firearm must not be able to close on a No-go gauge. If the bolt closes successfully on a No-go gauge, this means the firearm has excessive headspace and there is a risk of cartridge cases rupturing inside the chamber. If the firearm is new or recently repaired, it should be returned to the manufacturer immediately.

A used firearm may be able to close on a No-go gauge, due to wear of the bolt and chamber surfaces. This means it should probably go to a gunsmith for repair soon — it may be possible to fire new factory ammunition in it until then, but reloaded ammunition is probably a bad idea. The firearm may malfunction on slightly out-of-spec cartridges. Here’s where the test with the third gauge comes in (especially for firearms built to military specifications). This gauge is the Field gauge. The bolt of any firearm, whether old or new, should not be able to close on a Field gauge. A bolt that closes on No-go, but not on a Field gauge, may be considered close to being unsafe, but may work on new cartridges. Likely, it should be sent to a gunsmith to have the headspace reset. However, if the bolt closes on a Field gauge as well, then it is not safe to fire and should be sent for repairs immediately.

Chamber gauges

Another type of gauge that enables headspace (and many other dimensions) to be checked is the slotted gauge, for example those made by Sheridan Engineering. These replicate the dimensions of a SAAMI specification chamber. Inserting a round of ammunition into such a gauge allows you to see if it fits and, if not, which is the dimension causing the ammunition to foul, and where.